- Home

- Matt Stewart

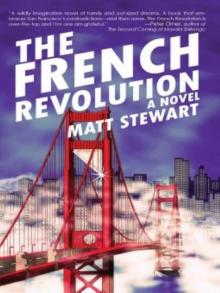

The French Revolution Page 3

The French Revolution Read online

Page 3

“What’s going on? Ezzie!” Jasper’s voice was so kooky when he screamed, akin to that of a female dwarf, and Esmerelda almost found a way to laugh despite the earthquake in her loins. “Open this door or I’ll bust it down!”

It was silly to hear him say that, and not just because of his voice—even if Esmerelda hadn’t been experiencing the most belly-busting pain of her life, hauling her big butt over to let him in was a physical impossibility after her hours of exertion. But his energy was infectious, his resolve admirable, his conviction inspiring, if mildly frightening. As she listened to his puny shoulder thump feebly against the door, Esmerelda was moved to action: she forced her dipping muscles inward, compressed her stomach, strained her hidden abs, and bobbed up and down on the toilet to loosen things up. Jasper heard her travails and took on a fresh determination in his ramming just as the police arrived with weapons drawn and ordered him to freeze: his assault on the bathroom not only constituted the destruction of private property but also was a textbook sign of an abusive relationship what with the hysterical woman inside. Seconds later the gas station attendant dredged up the backup restroom key from under a pile of invoices and yelled over for everybody to cool down, he’d let them in, when the mother of all hollers rangout from inside like agony incarnate, a dead dog on a doorstep. Jasper skidded to a stop and examined the door, assessing its breadth, its material construction, its hinges, possible weak spots. Another second tocked by and his head was down, he was charging, wild-man frenzy starring his eyes, snot foaming in his nostrils, legs churning smoke, glottal Hungarian consonants pouring from his throat, inducing the cops to panic and open fire. With a stiff crunch the restroom door gave way and Jasper barreled inside, falling at a fortunate angle that eluded the two bullets slicing after him and landing on the floor to get the first look of his daughter’s head peeking out from between Esmerelda’s legs, slick with blood and wailing like a walloped cat.

“Goodness,” Jasper said as he wrapped the girl in toilet paper. “Is this my doing?”

“That’s not all,” Esmerelda said, reaching for the grab bars. “Kid’s got company.”

A minute later a boy was out too, dispensing train-whistle shrieks and spraying scum water from his eyes. Alerted by the racket, Karen Winslow climbed down from the minivan to find Esmerelda hyperventilating in a lump on the floor, Jasper rubbing her back, the cops wiping clean two writhing brown bodies with handiwipes from Esmerelda’s bag, and the gas station attendant fingering a pair of bullet holes chest-high in the wall.

“Babies! That’s wonderful, dear. I thought you were taking your time for a number two.”

“They’re mine, Ma.”

“What?”

Esmerelda’s desolate silence confirmed it.

“Jasper! I didn’t even think you could, you know, were capable of—”

“This eraser can shoot lead, isn’t that right Ezzie?”

“Apparently.”

“So,” asked the gas station attendant, “whatcha gonna name them?”

“At midnight, the radio says it’s Bastille Day,” Karen noted.

“July 14,” Esmerelda said. “Yes.”

“What’s that?” Jasper asked.

“It’s the day in 1789 that French regular folks took up arms and busted some prisoners out of jail,” his mother said. “Radio said it started the French Revolution.”

“Guess you could call this a jailbreak,” Jasper said. “How about French names then?”

“Shoot, honey, I can’t remember those names on the radio.”

“Marat,” Esmerelda said.

“Yes, yes, that’s one of them.”

“Heck, I’m out,” said Jasper. “Pierre’s the only French name I know.”

“That’s it, dear. Robespierre’s another revolutionary.”

“It’s settled,” Esmerelda blurted. “Marat and Robespierre.”

“Which one’s the boy and which is the girl?” posited the gas station attendant.

“Who cares?” Jasper’s face drew thin and skeletal, ghoulishly framed by his patchy day-old beard. “What matters is will they have to spell out their names over the phone their whole lives. We can’t call them Matt and Robeswear. They’ll be cursed.”

“My children are named Marat and Robespierre. And that’s that.” Esmerelda fell asleep decisively as emergency vehicles screeched into the parking lot and a team of paramedics hustled to remove her from the toilet. She looked so peaceful amid the EMTs’ buckling knees, Jasper observed—her lips and eyes arranged in a slack, nonangry state of rest that implied some level of contentment—and he realized that in some way he’d given her this. With fingers crossed he willed her from falling off her stretcher, creating invisible guardian angels and well-padded cloud safety barriers with his mind, so intent on protecting her from harm or discomfort or accidental contact with anybody who wasn’t him that it took a few seconds to realize the gas station attendant was speaking in his direction. “Take this for your wife,” the guy was saying, pressing a carton of chocolate bars into his hands. “She’ll need the energy later.”

Jasper grabbed the candy instinctively as he hopped aboard the ambulance, trying hard not to betray the daffy mental disposition the attendant’s mislabeling had cast upon him. Mistaking Esmerelda Van Twinkle for his wife! And him, a husband! Provider, man of the house, coming home to a peck on the cheek and a homemade dinner—or, in Esmerelda’s case, he realized, a coupon-ordered smorgasbord, but still, warm food—then tucking in the kids and conversing about the events of the day and maybe dipping into her honeypot before nodding off on their king-sized bed. He expanded the scenario into greater detail over the course of the ambulance ride, with assorted lingerie and tubs of Crisco, until his knees began shivering and his mouth filled with slobber. Upon arrival at the hospital, he gamboled after Esmerelda’s stretcher with the full vim of matrimony, energetically introducing himself to medical staff as Esmerelda’s husband.

“What beautiful children you have, Mr. Van Twinkle,” a nurse told him as he watched his boy and girl wriggle on the other side of the nursery window.

“Well, they’re our first ones,” said Jasper, who was trying his best to find beauty in their alien mahogany skin but wasn’t having much success.

“They’re darling. Listen, your wife gave me their names, but I’m not clear on which is which. Marat and Robespierre, right?”

“Sure,” Jasper said uncertainly.

“Well?” The nurse pointed to the bassinets, one blue and one pink.

“Uh, boy’s the first one, Matt.”

“Marat?”

“Yeah, Marat. And then, Robeswear’s the girl.”

“Robespierre Van Twinkle. That’s a superstar name if I’ve ever heard one.”

“Hey,” exclaimed Jasper, who was far more intrigued by the boy himself, a possible rapscallion apprentice, future defender of the Winslow name. “What about Matt?”

“Wasn’t Marat the one they killed in the bathtub?”

Jasper nodded politely.

“Keep your eye on that one. He’s got some kind of karma on him.”

Jasper wasn’t sure what karma meant, but, judging from the nurse’s somber delivery, guessed it was some sort of waterborne illness that afflicted infants. He broke off in a wailing canter down the hall, flapping his arms like an ostrich attempting flight.

“Ezzie!” he exclaimed, rushing into her room. “Nurse told me the boy’s got karma! What are we gonna do?”

“Oh, for heaven’s sakes,” Esmerelda said sleepily. “We’ve all got karma, Jasper. Settle down.”

Jasper realized that karma might be one of those tricky medical terms for hair or toes or something standard. “Uh, just wanted to let you know, Ezzie. He’s got karma, just like everybody else. Normal boy. That’s good, having karma.”

“As long as it’s the right kind, the kid’s gonna be OK. Now make yourself useful and run down to the mess. I’ve got a hankering for steak, and jelly rolls if they’ve got ‘em.”

&nb

sp; “Sure thing, babe,” he said, and kissed her molten forehead. Entrusted with errands, a family under his care. Music flooded his head; he started whistling one of those festive French songs, a cancan, driving accordions and feathery hats and ladies kicking up ruffled drawers. Duh duh, duh-duh-duh-duh duh duh, duh-duh-duh-duh duh duh. The breathy skip-beats grew louder as he rode the elevator down seven flights and hopped over to the cafeteria, and turned sweeter and more vibrato-heavy as he reviewed the laminated menu stuck to the wall. He was working his way through the side dish offerings and puffing blue notes when little slips of cognizance daisy-chained in his head.

Battered onion rings. Sounds pretty good. Battered. What is that anyway? Beer-battered? Funny, beer in a hospital. Or just batter, like floury watery shit?

Here, batter batter batter.

Batter up.

Bastard.

The tooting trailed off. He bolted from the cafeteria and leapt up the emergency stairs two at a time, sped past his children snoozing in their bassinet showroom, dodged a docked gurney, whipped around a corner, and, after knocking over a cart of cleaning supplies, slid into Esmerelda’s room, took a knee, let it fly.

“Ezzie, would you, uh, do me the honor of, you know—”

“Haronk! What are you doing down there, Jasper? Get up where I can see you. You freak me out with stuff like that.”

“Look, Esmerelda.”

“Unh?”

Her eyelids creaked open, revealing bloodshot eyes, interminably tired eyes, heavy and hazel and growing increasingly more peeved at Jasper’s inability to string a sentence together.

“Let’s get hitched.”

“Not funny, Jasper. I’m going back to bed.”

“I’m serious. Married, you and me.”

“Forget it. We’ll have some legal wrangling for the kids, but marriage is out of the question. Anyhow, there’s no wedding dress around that can hold me.”

“Well, we can make one. Mama’s a whiz with the sewing machine. Besides, I know you’re a lot to love—and here I am, first in line.”

“I told you, kiddo, no.” She rolled onto her side. “Now let me catch some z’s, would you? Giving birth takes a lot out of a girl.”

He massaged her neck until she fell asleep, then trudged to the nearest bathroom and locked himself in. An hour later he stumbled out, destroyed. His clown shoes were scuffed up, the soles flapping off; his gummy shoelaces were chewed through in several places; his overalls were torn and stained red and yellow, a button missing and a snapped strap drooping like a limp pickle. His paper cap: well, forget about the cap, as torn up as it was, the top shredded, the white paper turned the color of deep-sea mud, the thin plastic cord under his chin long gone, the cap staying on his head only because after twelve years of distributing coupons his hair fit inside it perfectly, grew into it actually, tucked in tight as sheets on an army cot.

When the nursing staff saw the wreck of a father emerge from the bathroom, his face ripped with melancholy, his uniform in tatters, his feathery blue eyes strafed with woe, they looked away, toward the wall, at their watches, into their computers and waiting room magazines. Slowly they began to cry.

The karma-mentioning nurse started it because she was a crier, always had been. At weddings, funerals, baby showers, going-away parties, she cried, and she cried a lot at work from the joy of seeing newborns every day, with the occasional still-born or mother dead from complications drawing fierce tears of horror from the dew of happiness. Seeing Jasper’s face kicked it off, associating him with Marat and Robespierre, recalling his entry to fatherhood, weeping happy tears.

Then she got a good look at him. Absorbed his mutilated garments, his vibrating throat, his thin, failed lips, his pallid skin. His smile jarringly absent.

She cried harder, reached for him.

Her best friend on the shift, Stacy, while not a crier, couldn’t help being moved by Jasper’s mournful appearance, because not only was his hangdog face pitiful, but also, before nursing school, she’d worked as a legal secretary in a law office in a converted Victorian on Noe Street and had seen him around all the time, the Coupon Man, smiling and handing out coupons and sometimes balloons on Market Street, often opening the nonmechanical, narrowish metal door at the local print shop for her when she had to run off some copies. His defeated face was tragic and wrong, and she too felt tears wetting her cheeks.

Soon the other nurses on duty were whimpering by the nurse’s station—they weren’t sure why and didn’t much care, just went with the flow and let their troubles pour out—and then the secretaries and administrators were sniffling too, stuck in the muck of collective gloom. It jumped to the patients next, picking them off one by one: tough old men with the end in sight finally breaking down, cancer patients purging pain from their bodies, depressed teenagers terrified by life’s apparent meaninglessness. Sorrow trickled down the hall alongside Jasper’s slump to Esmerelda’s room, his presence instilling heartache in every life-form he passed. Even the visiting dog from the SPCA got glum, as glum as dogs can get.

Esmerelda Van Twinkle, tough as burned bones, a hellcat, a coldhearted bitch and proud of it—and still the peals of lamentation got to her. She was wiping her nose and trying to read a day-old newspaper when Jasper slinked into the room.

“Jeez! Did you get hit by a bus?”

Jasper closed his eyes and sighed with such flourish that anyone who didn’t know him would have assumed he was being theatrical. Esmerelda, however, was aware of his gigantic lung capacity and knew that his exhalations were honest and troubled. Her nose widened into a mushroom as she succumbed to the tearfest, the hot saline drops cascading down her puffed cheeks and over her seven chins until absorbing into her hospital gown.

“Ezzie, look.”

“You’re in a bad place, man. Taking me with you. Hand me my bag.” He carried it over from a chair along the wall and stood beside the bed as Esmerelda fished out her sapphire-encrusted scissors.

“Come here.”

He sat down on the mattress while she fiddled with her remote control and moved the bed upright. After a couple of power failures and a system reboot provided by a sniveling nurse, Esmerelda was able to reach him. Sliding the scissors beneath his paper cap, she wove the blades around his coiled gray-black hair, slicing a jagged line from his ear to the crown of his head. She peeled off the aged headpiece with uncharacteristic caution, unveiling his plateau-shaped hair formation in slow, sticky chunks, as if removing an old bumper sticker.

“There. Now you can breathe at least.” Slurps and drips; she hadn’t stopped crying throughout the operation.

Jasper pulled at his earlobes and blew out breath like an industrial air conditioner. “Ezzie, what’s not to like about marrying me? I got a job, I’m a good man. And I’m crazy in love with you too. Bottom of my heart up to the top. All the way.”

The wounded noises down the hall softened, replaced by honks of nose-blowing.

“Not now, Jasper. Let’s get used to the kids first, OK?” Esmerelda turned a bleary eye to him and tried to nod, an already difficult procedure with the seven chins made impossible by the rain-swept conditions. Jasper got the point, though, and sat quietly stroking her hair while patients all around them called out for more tissues.

Shit if she wasn’t a tough nut to crack.

When Esmerelda tried to slip into the house with her children, her key no longer fit in the lock. She hammered the anchor-shaped knocker until lights came on upstairs.

“Yes?” The door cracked open four links on the chain. Fanny Van Twinkle peered out in a zebra-striped bathrobe, a triple martini in hand. She was of average height, a few extra pounds in the trunk but certainly not fat, with wavy gray hair recuperating from a lifetime of homemade perms. Her onion-shaped face contained even brown eyes flecked pink from gin, a drooping nose, medium-sized ears like apple slices, vampire lipstick wound sloppily around her mouth. Her fine lips parted and she started to cough, a broken carburetor firing up.

&nb

sp; “Hey, Ma,” Esmerelda said. “Door’s busted.”

“I changed the locks. An unbalanced African American man recently assaulted me in the living room. He tried to hug me and called me Ma. It was very upsetting.” Fanny pointed to the two blanketed lumps under Esmerelda’s forearm, alternately crying and snoring. “What have you got there?”

“Babies. My kids, technically. Just bringing them on home.”

“Your kids. Technically.” Fanny knocked back half her martini in a soundless pour. “Thank you for the update. Heaven forbid I was not still your landlord—I never would have been informed.”

“It’s not that, Ma. They were a surprise, to me even.”

“And the father?”

Esmerelda sighed. “Can I come in first?”

“No.” Fanny pulled her bathrobe tight and smiled.

“What the hell’s wrong with you? These are your grandchildren.”

Fanny wrinkled her heavy nose at this, her daughter’s endless entitlement, the ache that never ceased. “I gave birth to one child already, and you are still here. I have paid my dues, and for what? Ignorance, disdain, all of the above. If your father were here to see this—humph! You may stay, but those mystery children are not welcome in my home.”

“You’re kidding, right?”

“Have I ever kidded you once in my life?”

There was no one to call but Jasper. “Here,” Esmerelda said, “you started this mess. Take ’em off my hands until I can figure something out.”

“But Ezzie, they need their mama.”

“Lots of kids go a day or two without their mom. They’ll live.”

“Girl,” he whispered, “they gotta suck on your titties to eat!”

“Dang it,” Esmerelda admitted. “You’ve got a point.”

Jasper telephoned his mother, and an hour later all three generations were strapped in the minivan and speeding north along the Great Highway, past the gas station birthplace and the pounding Pacific and up the fog-snuffed hills into the Presidio, Jasper’s apartment on Stillwell Road.

They pulled into a cramped parking lot and parked next to a stairwell. A hard buzz ran through Esmerelda, and she began rapaciously picking a zit on her forearm. “There an elevator?” she asked.

The French Revolution

The French Revolution