- Home

- Matt Stewart

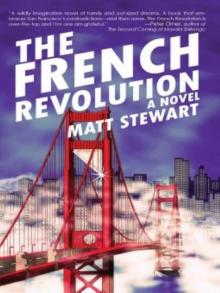

The French Revolution Page 6

The French Revolution Read online

Page 6

After another circuit around the living room, he lowered himself onto the sofa and provided running commentary on an oscillating love triangle, three Swedes covered in raspberry jam and tongues. His stubbled cheekbones bit through the half-light of the dangling kitchen fixture, a hard gibbous moon that moved Esmerelda’s clitoris a step closer to activation.

A minute later, Sven discovered a ham-bone forearm spider-climbing up his leg and let slip his first thought:

“Ya, big gurl, ready to play?”

Was she.

Her hand raced through its ascent and snatched Sven’s harpoon. She took a long pull on his flask and bathed his rigid weaponry in a thorough vodka wash. After a few minutes of toothy lathering Johan got jealous from being left out of the fat-girl fun, so he raised her muumuu from behind, parted her whale cheeks, and dove in. The lasses wandered over intrigued, bringing their coterie of crotch-pumpers with them, and in a few minutes Esmerelda was completely covered in Swedish swingers. Somebody sliced off her muumuu with the blue-jeweled scissors from her great wool bag, and no sooner was Esmerelda’s celestial nudity unveiled than it was consumed, entirely, exciting her sexual soul into a placid, perfect trance.

It was Marat’s first night alone in bed, and he dreamed of cartoon devils dancing around him, poking his face with hot brands, spitting black lava. The door to the bedroom swung open, Hades light filtering around a one-armed monster.

“Alo? Helvete, this ain’t the loo.”

The monster left, the door was ajar, sugary pop music leaked in. Marat climbed to his feet and stepped through the vortex to another universe with

naked people lumped together in a pile

crazy mixed-up yelling

men thumping against women with their hips, spanking them

He ventured delicately into the room, staying in the shadows. The dream was so vivid it smelled. He saw his mother in the center, her head knocking about like when the Gargantuan hit a speed bump, her neck wild with sweat. Her mass of skin disruptively pink, outlining the moaning white-skinned ghosts in orbit around her.

Her eyes drifted over him, stopped, and blinked thirty times before Marat could move.

The monster grabbed him, hoisted him over his shoulder, threw him back in bed, and told him to stay put, buster, no sneaking out. Furniture scraped outside; the door wouldn’t budge. For ten minutes he heard boots tromping and low gargled voices, the music cut, glass crashing, then quiet except for his mother’s distinctive sobs, rumbling and endless, as if they’d run out of string cheese.

He woke up in his new bed to the staccato beeps of the special services van, the nightmare haze unforgettable in the back of his pixilated head.

THE TENNIS COURT OATH

On June 20, [the revolutionaries] took the famous “Tennis- Court” oath, “to come together wherever circumstances may dictate, until the constitution of the kingdom shall be established.”

—JAMES HARVEY ROBINSON,

Medieval and Modern Times

The real event of the Tennis Court was to unite all parties against the crown, and to make them adopt the new policy of radical and indefinite change . . .

—JOHN EMERICH EDWARD DALBERG-ACTON, Lectures on the French Revolution

On their third birthday, Esmerelda dressed the kids in matching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle sweat suits and took them to the zoo. Feeling optimistic after her recent slight but statistically significant weight loss and her relative success at single motherhood, she left the Gargantuan at home. It was a mistake: the fog made her knees ache; her shin splints fired up on the hike from the bus stop to the ticket window; after a minute of sustained walking she barely had the strength to hang on to her walker, a loose knuckle away from a sidewalk sandwich. Robespierre and Marat ran ahead to look at the giraffes and great apes, climbing onto fences and digging half-eaten cookies out of garbage cans as Esmerelda gulped distilled water from her bag and humped over to the first-aid station. Fortunately, Esmerelda thought, as she announced their departure fifteen minutes later, they wouldn’t remember a thing—a prediction that proved true with the exception of the roaring lion, which embedded itself in the bedwetting dreams of both twins for weeks to come. They took a cab across the street to the Carousel Restaurant, where a waiter planted candles in matching cheeseburgers and sang “Happy Birthday” in a faux French accent.

“This is why we live in San Francisco, kids,” Esmerelda said. “Appreciation for the arts.” But her children ignored her, lost in slurry tears from the cut of the waiter’s soda jerk cap, which looked as if it had been stolen straight off the head of their father. The crying did not stop for hours.

After a few seasons in a nursery for abandoned infants, drinking formula overstock and wearing coarse municipal diapers, Murphy was placed with a Korean foster family in Wheaton, Maryland. It was a nondescript, two-story, off-the-rack home: three bedrooms but housing ten foster children, with two stacks of bunk beds in each kid’s room plus a pull-out futon for the inhabitant with the most seniority. The Ahns aimed for full capacity to maximize their tax shelter, which translated into long lines at the bathroom, irregular feedings, plenty of name-calling, pinching, theft, brawls over the remote control, and whole meals stolen off plates, with close to zero in the way of basic supervision or instruction. Early on Murphy developed a system to keep himself fed, whereby he stuffed handfuls of rice from the cooker into his mouth until he spat up tapioca. After a series of blue-faced near-choking experiences, the Ahns figured out his racket and tried to scare him out of it, pointing out the health consequences in simple child language: stop breathe, no move, die, boom. But then the phone rang or a customer came to the register at the minimarket they owned, and as they slung him onto their shoulder and ran their business, his transgression forgotten, he watched the world watch him get away with whatever he wanted.

As the years passed, he graduated from rice to candy, consuming small hills of sugar that jolted him into hyperspeed and laid the foundation for a lifetime of skin problems. At least one body part was always jiggling, creating an aura of anxiety and shiftiness, his image less than trustworthy. He was unable to read anything for more than fifteen seconds, exploding with a combination of poorly executed gymnastics and undisciplined kung fu, rambling from the kitchen to the living room to the toilet, often extending out to the yard and into traffic. Chocolate captivated him; he blew his entire two-dollar allowance on Kit Kat bars and M&M’s pounder bags that he hid from his foster siblings in the bottom of his bed, until his pediatrician told the Ahns to cut him off, at which point he resorted to stealing. On a Saturday morning in broad daylight, surveillance cameras at the Ahns’ convenience store captured Murphy jamming Mounds bars down his pants from three different angles; he was apprehended on his way out of the bathroom, his lips smeared brown, wrapper shreds in his pocket. They questioned and requestioned him in the manager’s office, and when he refused to confess, they showed him the incriminating footage in super-slow motion. “Not me,” he repeated in a dour voice, “not me.” When they eventually took him home, he ran straight to the kitchen and shoveled rice down his throat until it all came coursing back up.

Murphy was spanked, then grounded. But he held his position, repeating that it wasn’t him, it was a case of mistaken identity, he’d been framed. He insisted so loudly and fervently that his foster parents, Marvin and June Ahn, started to wonder if there had been some kind of misunderstanding; maybe another kid in the store that afternoon had the same Washington Capitals T-shirt and buzz cut, the same addiction to sucrose. It wasn’t impossible—the video was black and white and grainy, and Murphy was so vehement, his sense of injustice so furious, that Marvin and June, after dispensing tough love to dozens of misbehaving foster kids, ended the grounding after only two days.

The next afternoon Marvin found Murphy out behind the dumpster with a carton of Reese’s Pieces, his fingers stained with candy coloring, his breath sickly with corn syrup. Marvin was halfway through imposing a double grounding, with i

nterest, when Murphy observed that he’d seen a big furry rat run along the grout. Maybe he should tell the health department—they could shut down the store, and that would really suck. Marvin grabbed the candy and shoved the kid into the office, amazed by the extent of the seven-year-old’s ability to believe his own bullshit, his wanton dearth of innocence. In his years of foster parenting, he’d seen plenty of lying, name-calling, theft, and general loutishness, but blackmail was a first. And extra-alarming from a kid who could barely form complete sentences.

He put Murphy to work building a display out of expired soup cans and flipped open the Pepsi calendar on his desk. September. Maybe there was a way to get him in a football league. Not a team guy but hardheaded enough to be useful; open-field tackles and wind sprints were just the thing to burn off this edge. He checked in on the soup-can display, rising into two tall twisting staircases boxed in by Doric columns, a palatial grand foyer. Murphy lay on the floor working on stylized trim arrangements, gnawing on a pack of Rolos and working on his side kick. Martial arts could work, possibly boxing, and Marvin scanned the Yellow Pages for nearby training gyms until he heard a leaden collapse, dumbbells rolling off a sawhorse, soup cans rolling in eight directions, Murphy standing over the pile with chop-hands ready, favoring his left foot after what was likely a leaping round-house. Marvin threw the phonebook on the ground and watched the kid bounce out the door and across the parking lot, a whirling dervish yipping imitation Japanese, throwing Bruce Lee double jabs as candy corn spilled from his pockets. Last thing Murphy needed was mugger training, Marvin realized, and instead decided to tire him out the old-fashioned way: floor-scrubbing and shelf-stocking and all-purpose ass-licking; work him till his feet swelled up his sneakers.

For four years Fanny lived alone in the modest banana-yellow house where Esmerelda had grown up, a block from the beach and within walking distance of the elementary school. The solitary space swelled with the morning of April 1, 1979: a bowl of oatmeal at 4 AM, an extra spoonful of brown sugar, a ham sandwich and an apple in a paper bag for lunch, a last scrape of her husband Harold’s chapped lips against her forehead before the day’s fishing expedition to the Farallones. The door shutting on a creaky hinge, which Fanny oiled immediately lest it wake up Esmerelda. Harold’s truck coughing into the fog. A rainy day of soap operas, cleaning, grocery shopping, a hot bath. Dinner in the oven, Esmerelda doing homework in her room. The doorbell. A police officer describing squalls, dropped radio, Harold’s skiff miles off course. The Coast Guard out in high seas, floodlights beaming over whitecaps. Two days later they found Harold’s signature green net shredded by the sea.

The strike to her chest, her husband stolen away—part of her forever, a tattoo around a bullet hole. April 1, 1979, April Fool’s Day, no joke.

Fanny wore the same clothing, ate the same food, lived in the same house, received the same amount of Social Security each month. Every election cycle she voted for the same presidential candidate, though Gerry Ford had been out of contention for some time. She drove the same Mustang convertible with the same expired registration, refusing to submit to a newfangled smog test. She hadn’t approved when Esmerelda enrolled in the culinary academy, or landed the gig prepping pastries at the yuppie haven Incognito, or put on weight like a bear headed for hibernation, or started her worker drone job at the CopySmart flagship store, or showed up with her noisy pups and shipped out to Jasper’s Presidio apartment. But after a few months Esmerelda’s smell had wondrously evaporated along with her out-of-place clothing, modern music, perplexing street slang, and ineffective weight-management devices. Heavy ocean air and daughterless simplicity seeped into the house, cigarettes and gin propping Fanny aloft.

In the summer of 1994, she began receiving letters in Esmerelda’s handwriting folded over photographs of brown children, a cute girl and a chubby boy smiling and scowling, both with Harold’s bean-shaped eyes. In early August she received a phone call inviting her to supper at the Cliff House, and though she thought she knew better, when Esmerelda reported that her kids were getting into fishing, dropping poles at Lake Merced on weekends and digging for their own night crawlers before school, curiosity got the better of her. Esmerelda met her at the restaurant with a trembling hug and, after confirming Fanny had brought her checkbook, began narrating an eight-course eating extravaganza with tales of her missing husband, her monstrous credit balance, her years-overstayed guest status, the depravity of Little Stockholm hedonism. Her jaw-dropping grocery bill. The final decision of the city’s eviction board, notice served by the sheriff’s department. And the logical point that there were unused bedrooms in Fanny’s house.

“I do not think so, dear,” Fanny said, cooling her after-dinner tea with a nip of gin from her purse. “You are a big girl; you can take care of yourself.”

Esmerelda softly gargled her water. She had forgotten her mother’s snooty refusal to use contractions in speech, as if efficient diction was a mark of baseness.

“Ma, I need help.” Slow, measured tea bag dips. “I do not think it would be a good decision. I do not like changes to my household, and the way things are suit me fine. Your tornado children would create a tremendous ruckus, and why should I put up with it? Besides, you left me in the first place. So.”

Esmerelda dug her nails into her knees and waited for the urge to throw her silverware at her mother’s face to peter out. Eventually: “I didn’t want things to come to this, Ma. I know what you’ve been through, and believe me, I miss Dad too. But I gotta set things straight. First, I didn’t leave home because I wanted to. I tried to bring the tots home, but you wouldn’t have them—”

Fanny loudly tore open a sugar packet with her teeth and dumped it into her tea.

“—truth is, you’re my only family. I’m in a bad place: my hubby up and vanished; my kids growing up in Orgyville, USA; work all day and kids all night and still not enough cash to cover expenses. And the sheriff’s going to forcibly remove us tomorrow. So, Ma. Please. Let us stay with you.”

Lumps of perspiration lazed on Esmerelda’s brow. Fanny was perplexed—she couldn’t remember the last time Esmerelda had said “please”—and somewhat swayed, her heart the tiniest bit thawed.

“You understand, Esmerelda, I am the boss. Things must remain the way they are. No changes whatsoever. That means you may not replace my classic furniture, or put your hideous modern music on the phonograph, or, heaven forbid, exchange my tasteful stores of clothing with the whoring outfits I see on the streets.”

Ezzie nodded frantically, hair snakes snipping free from her bun.

“My word is final. If I ask you something, I expect it to be done right away. Not after you are done with your pizza or your gallon of ice cream or whatever it may be. Immediately.”

Yes, said Esmerelda’s shaking eyes, I’ll carry you on my back over continents and across solar systems if that’s what it takes.

Fanny extracted a ream of paper from her own massive wool bag and thumped it on the table. “I anticipated that you might want to move back in, and took the liberty of calling my attorney, to have my conditions written out.”

The stack ran fifty pages deep, single spaced, a hard block of information and clauses. Esmerelda flipped through it, scanning first sentences and whistling appreciatively. Whereunto. Whereas. Be it agreed. Whatever. She dipped into her bag and groped for a writing implement.

Fanny swatted her elbows. “Read it first! I thought I drilled some sense into that noggin of yours.”

“I’m moving in, not signing away my life. Ain’t like I’m buying a house.”

“Oh yes you are, dear.” Fanny slipped a butter knife into the sheaf of paper and terraced off the top third. “That is part of the contract, section five. If you choose to relocate yourself and your offspring into my home, you must buy a house to leave. Not just any house either—a house in the city of San Francisco, with a bedroom for each inhabitant, and within three hundred feet of a park. A sound investment. I will not have you squander your

money again.”

Outside, a black Town Car glided into the parking lot, piping smooth jazz at a firm volume.

“A house? I work at a copy shop, Ma. Not really in the house-buying income bracket.”

“It is high time for you to own something. This day-to-day nonsense, this absurd employment making photocopies, well, you are walking in place. You need a career, not a job. It is time to buy into something, to set goals and achieve them. The baking was a start, but you let yourself be pulled astray. Get it together, dear. It will make you a stronger, more focused woman. To achieve and accomplish, these are the traits missing from your constitution. Please, moving back in with your mother? It is the life goal of very few people.”

Esmerelda clenched a smile. So many counterarguments burning: she’d just been promoted to assistant manager, what a lot of people called a career, thank you, even if it wasn’t exactly the gig she’d always dreamed of; raising her kids right was a goal, a darn good one; and anyway, Fanny hadn’t worked a day in her life, just scooted forward on the life insurance and government checks.

“I am sure that you are thinking about the many ways in which you benefit the world. You have two children, neither of whom appears to be deformed or unhealthy according to the photographs I received. To which I say: welcome to the club, dear. And what is more, your attitude toward the children appears to be that they are the ropes keeping you tied to the dock. But it is not apparent that you were going to leave the dock in the first place. You require motivation, a destination for your voyage. A house is a practical place to start.”

The French Revolution

The French Revolution