- Home

- Matt Stewart

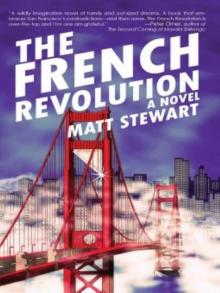

The French Revolution Page 9

The French Revolution Read online

Page 9

“We’ll tape it. C’mon, this’ll be fun. I’ll give you your own walkie-talkie, and a billy club if you’re good.”

“Michael Jackson!”

After a few minutes of repeating the arguments to each other, Marvin Ahn shouldered open the door and hauled Murphy down to the car. They drove three blocks to the store, where Murphy soon lost walkie-talkie and billy club privileges for screaming the lyrics to “Beat It” while parading up and down the parking lot like a mad ghost, his ultrashort haircut appearing unsettlingly close to premature baldness in the mystical, century-changing gloom, his off-key falsetto haunting shoppers and employees alike. The platoon of shop owners yelled at him to pipe down, stuff his ugly-ass piehole, go back to the carnie camp he came from, but Marvin stepped in and sensibly explained:

“Think of it this way, gentlemen—he’s a walking alarm. Nobody’s going to mess with our stores with him out there rousing the dead.”

The boy’s head popped in the doorway, shouted out the opening lines to “Billie Jean,” and vanished.

“Bullshit excuse,” replied Tasos Mitrakos, who was Greek, rude, and an excellent barber when sober. “You couldn’t control him even if you knew how.”

“Patience,” Marvin insisted, but a fuse activated in his liver and he begrudgingly recognized that Tasos was right.

Midnight slipped away without mayhem or looting bandits, all glass plating intact and free from graffiti, electricity still functioning, siren free. Murphy sang “Thriller” twenty-one times from when they started keeping track at 10:30, giving comic-store owner Ben Marg the betting pool win. Graciously he plowed his winnings right back into their New Year’s celebration, sparkling cider and packaged cakes from Marvin’s store, pickles and sandwiches from the deli, tambourines from the Music Emporium, toothbrushes from the commuter dental office. After sitting on the curb for a while and listening to the festivities, even Murphy came in for a Dr. Pepper, whereupon he stumbled on pile of hangers from the dry cleaners which he used to sculpt wire figurines of cops and robbers and guns of all sizes.

The car worked on the first try, the ride home was uneventful, and the immediate perusal of the videotaped countdown confirmed that “Thriller” had been selected as the number-one music video of all time. June Ahn, who’d moved most of her vintage tables into storage but ran out of time for her Pembroke set, shook like a set of maracas when the announcement came on.

The next morning at 7 AM, Marvin Ahn drove to the store and parked in a field of shredded candy wrappers. Black spray paint scarred the sign for Ahn Minimarket: a loopy FUCK, a meandering YOU, a bulging AHN. The window frames were ruptured and glass shards mined the floor. A flock of pigeons clumped in the doorway, pecking on burst packages of chips. Kalamakis’ barber pole stuck out of a soda cooler. Lumps of gum were nailed to the ceiling and the candy aisle was empty. Marvin Ahn tiptoed into the punctured storefront and past ransacked shelves, leaking refrigerators, a smashed hot-dog-warming machine. The cash register was gone and the safe sprung, the only clean spots in the place. Along the inside walls, more graffiti spooled from the floor to just about the height where an eight-year-old boy could reach.

LIVE! LIVE! LIVE! LIVE! LIVE! LIVE! LIVE! LIVE!

The effect upon Marvin Ahn was oddly uplifting. A believer in the power of positive thinking, he found himself nodding to the affirmative message for a few seconds until he went behind the counter and saw the framed photographs of his parents back in Korea rubbed out with spray paint. He called the cops—“How did you guys miss this mess? You blind or something?”—and briefly wondered if the “Live” message could implicate some kind of left-wing health food movement, his fat- and cholesterol-heavy snacks scapegoats for the entire fast-food industry.

Investigator Rodriguez and Officer Bindle came by the house in the afternoon. June made coffee and warmed up some muffins.

“We think it’s an inside job.” Rodriguez peeled off a muffin top and nibbled the perimeter. “That safe was opened—nothing broken at all. All the pins are intact, meaning somebody knew the combination. They also knew how to disarm the security system, climb up to the surveillance cameras, and spray-paint them without getting caught on tape. But getting into the safe so easy—that’s the clincher.”

“All the employees got alibis,” Bindle said. He was shaped like a surfboard, lean and tall with coarse features that suggested regular childhood beatings. “No witnesses neither.”

Marvin silently thanked his insurance broker for convincing him to up the coverage the previous fall. “No leads at all?”

“One thing. We figure you’re coming out pretty good on insurance. And not much in the way of alibi for the middle of the night.”

“Please,” Marvin whined. “Tell me you’re not doing this.”

“Let’s have a talk at the station.”

“Can it wait? The repairmen are coming in half an hour and—”

He felt Bindle behind him, six foot eight, 240, clipped mustache and pebble eyes, no capacity for sarcasm. A regular at the Ahn Minimart, his proclivity for Hostess products had earned him the nickname “Cop Cakes” among the night-shift guys. “Let’s go.”

At the station Marvin talked fast and passionately, detailing his commitment to rapid-sale merchandising, the recent renovations at the shop, his charitable donations, his work as a foster parent. Rodriguez bought it hard, and even Bindle started coming around when Marvin mentioned the ruined photographs of his recently deceased parents. The report from the county treasurer’s office came in as they were standing up to leave.

“Everything kosher?” Marvin asked, anxious to check on his repairmen before they ate his remaining inventory.

“Could be,” Rodriguez says. “Your tax records got flagged.”

“What?”

“Nineteen ninety-eight payroll. Know a Su-Jung Kim?”

“Yeah, she works for me.”

“You didn’t pay her payroll taxes. Same for Diane Wing, Jao Park, five or six others.”

“Let me see that.” Rodriguez slid over the papers, the names and numbers circled in red. “I’ll have to check with my accountant.”

“Not a big deal,” Rodriguez said. “You’re free to go.”

A month later, 80 percent of the store’s staff was laid off to free up cash for back taxes and penalties. Marvin and June retained only a heavyset brother-sister duo from Kensington who accepted minimum wage, a pair so emboldened by their scarcity that they treated the minimarket as their personal buffet, snarfing chips and hot dogs and ice-cream treats whenever they liked, often clocking out with a bag of free victuals to last them until next shift. Hiring trustworthy employees wasn’t easy in the minimarket cash game, where profit margins closely tracked the amount of time owners were on the premises; without loyalists manning the registers, Marvin and June spent nearly all their conscious hours sleepwalking around the shop.

No one objected when Murphy loaded up on candy and set to work on the tree house the boys had always wanted in the towering oak out back, lugging home overstock from the lumberyard and reusing nails from neighbors’ fences while Michael Jackson moonwalked in his Discman. He was handy and patient when it came to making things, able to wait for weeks as projects formed from pieces. At night he snacked on a feedbag of mini chocolate bars and watched COPS and LAPD: Life on the Beat, documentaries on famous criminals, heist flicks, drug-bust exposés, police procedurals. Within weeks an extensive library of law-enforcement-oriented media accumulated in Murphy’s bedroom, their retail value far exceeding his allowance.

After making a series of court appearances, negotiating a repayment plan, and settling a good chunk of their debt, the Ahns hired back two cashiers and took a day off to decompress. On their first day home, they didn’t find Murphy’s videos, stowed beneath a pile of shoes in his closet, but the big-screen television in the boys’ bedroom was hard to miss. “Wow,” said June, her matchstick hips curving onto Murphy’s futon, which had been widened and repositioned alone beside the wind

ow, made up in satin police-blue sheets and four fluffy pillows and a much thicker mattress than June remembered. “Nice TV.”

“Yeah,” Murphy said, slumped on his bed and sipping Pellegrino through a curly straw. Two of the younger boys watched carefully from the top bunks, suited up in tight haircuts and authentic Redskins jerseys like real, if miniature, gangsters.

“Thirty-two inches?”

“Forty-two.”

“Hmm.” She nodded. “Pretty big.”

“Bigger than the one downstairs.”

“You know, I think you’re right.”

They watched a minute of music video, Michael Jackson yelling and playing racquetball on a spaceship. “Did you win a sweepstakes?”

“Nope.”

“Murphy.” Her pigeon hand locked onto his shoulder. “Where did you get this?”

“My real family sent me some money, and I bought a TV with it. OK?”

In the distance a cellphone rang, a MIDI version of a semi-popular R&B song. “I’ve been a foster parent for fourteen years,” June began, “so don’t think you can—”

Murphy pulled a black plastic log from his pocket. “Yeah? Cool. Be right down.” The phone beeped off. “Gotta go.”

“Hold on. We need to talk about where you got this television. And the cellphone.”

“Circuit City. But I gotta go, my uncle’s outside.”

“Your uncle.”

“My real uncle. He called a couple weeks ago, while you guys were working.”

“I see. I need to meet this uncle.”

“Fine.”

One of the boys helped Murphy into a puffy Knicks jacket June had never seen before while the other held open the door. Out in the driveway, a scuffed-up ’82 Chevy Caprice grumbled and popped. A scrappy rat-tailed alcoholic-type leaned out the window, his smile a slice of rotten melon, his eyes bulbous and untrustworthy, his skin the color of Gouda cheese, wearing a denim tuxedo with cigarette packs loaded in every visible pocket. He laboriously pushed open the door, releasing the stench of water rot.

“Hey there, Murph!” The man got out, shut an eye, and shot a finger gun at Murphy. “Ma’am,” he nodded.

“Who are you?” June asked.

The man chewed his cheek and spat brown saliva onto the road. “Name’s Russell Taylor.”

“My uncle,” Murphy announced.

“Nice to see you,” June said, wondering how Murphy’d put the poor schmuck up to it. “You’re about a decade late.”

“Huh,” Russ Taylor said, not a fan of her tone. He was about to reach back to his junior boxing days to educate her about proper manners, when the kid got his attention with furious arm-waving and he decided the heck with it, mulligan. “My sister was Marisa Taylor, Murphy’s mom. I was in jail when Murph popped out, couldn’t take him in. Tell you the truth, finances what they are, can’t do it now neither. But I did give him some money the other day, help out a little.”

“Really.”

“We’re going to catch a flick and a milkshake. Care to join?”

“Uncle Russ!” Murphy kicked a stick and cracked it with his heel.

June laughed. “I need to see some identification.”

“You bet. Wouldn’t want you to think I’m part of some kiddie sex ring or nothin.” He took a plastic wallet from his jeans jacket and pulled out a Maryland driver’s license, peeling at the corners. Russell Taylor, Rockville, Maryland.

“I’m going to copy down your license number and address,” June said, “and run it with the police. That OK?”

Russell Taylor grabbed at his ID and missed badly, falling back on his heels with an arrhythmic bob. “Hang on a second,” he spluttered, “I ain’t done nothing wrong.”

“If you haven’t done anything wrong, you have nothing to worry about.”

“Chill, Uncle Russ,” Murphy said. He’d circled behind the stranger, June realized, and was holding him by his belt.

“Shoot, taking my nephew out for a flick’s tougher than busting out of prison. Not that I know anything ’bout that.” Russ chuckled and spat on the sidewalk, then came inside for a diet soda while June went to the den and called the station. Ex-con was right, battery and domestic abuse, but he’d been out and clean for five years. Looked like Murphy too, the same dermatology problems, chronic impetigo and acne. Unbelievable, but the story held up. She reminded Murphy to take his skin medication, nothing rated R, home by seven. They piled in, the Chevy chucked alive, and Russ Taylor rounded the corner in the direction of the Cineplex.

He pulled over three blocks later. “Here’s your money,” Murphy said, and dropped a ball of twenties in Russell’s lap. Russell scooped up the roll, tested its thickness with a quick squeeze, and began peeling off bills and piling them on his knee. He was three hundred in when Murphy swung open the door and eased out.

“Hang on,” Russell said. “What if it’s not all there?”

“What?”

“I said, what if it’s—”

“I heard you.” Murphy fronted his waxy smile. “What are you gonna do about it?”

Russell’s shoulders sharpened; his cheeks went dark. “Rip your faggot face off, you little twerp,” he hissed.

“Whatever,” Murphy said, “that’s the easiest grand you’ll ever make.” He hopped over to the sidewalk and set a course for the mall. At the next intersection he called up the Florida bank on his cell to check if the rest of the money had arrived, cash shipped certified mail, not the traditional way to make deposits but a quirk this financial institution had been willing to accommodate. Then a burger, a couple movies, a cab ride home. Maybe he’d pick up a can of paint for the tree house.

As he crossed the street to the mall he felt a flash of liquid against the back of his head, then a soft, metallic knock. He turned and saw the diet soda can on the ground, the Chevy peeling off toward the Metro station. “Two hundred short, assface!” Russell yelled out the window. “I’m coming back for it!”

Murphy walked to the median strip and sat down against a lamppost. Violence was the only response that came to him, violence against violence, violence against idiocy, clubs and kicks and immobilizing headlocks, like the cops on TV with heavy boots and backup. But Murphy knew he didn’t have backup; he was a troublemaking bastard orphan, and no adult would side with him against the out-of-work mechanic he’d found in the phonebook, the only person with the same last name dumb enough to take the gig. They wouldn’t even listen. Just another punk-ass kid.

He’d been on the cusp of insignificance ever since he was born.

He slapped the lamppost, swinging with open hands, the doggy paddle on land. He galloped over to the sidewalk and pulled down a NO PARKING sign, threw somebody’s rake into the street, knocked down a mailbox. He found a tricycle and slammed it against a driveway until he got kind of ashamed for fucking up a kid’s toy, threw it aside and took on a trash can across six front yards, head stomps and jawbreakers and bionic pile drivers and top-rope clotheslines and all the other wrestling moves he could remember, the one-sided smackdown slowly disemboweling his rage. As his body slowed, he realized this was the worst he’d felt since missing the top video spot live, the shit that started it all, his swan song repeated twenty-one times in the parking lot while the outside world fell lost in the synthesizer beats, the monster creep, the werewolf preening, the deranged cackles. He was capable of anything, and he stabbed an SUV’s tires with a garden trowel to prove it.

Live! Live! Live! Live! Live! Live! Live! Live!

All Murphy had wanted was to see the fucking video live.

LET THEM EAT CAKE

The time had arrived when the abuses of the old régime could no longer be tolerated, and sweeping reforms were demanded . . . The nation, hitherto politically a nullity, had awakened to a sense of its rights; while absolute sovereignty, with its arbitrary dictum, “L’état c’est moi,” and its right divine to govern wrong, had lost its prestige, and had apparently no prospect of regaining it.

—LADY CA

THERINE CHARLOTTE JACKSON,

The French Court and Society: Reign of Louis XVI and First Empire

If the people have no bread, let them eat cake.

—MARIE ANTOINETTE,

archduchess of Austria and queen of France during the Revolution, executed by the Revolution in 1793

Until the age of twenty-two, Esmerelda Van Twinkle was a regular-sized person, even on the skinny side during summers. She enjoyed bikinis and Spandex and salads, jogged three times a week before breakfast, and often went on bike rides over the Golden Gate Bridge and through the Marin Headlands, once all the way up Mount Tamalpais. She was the sprightliest of the chefs at Incognito, the only one without a bowling-ball belly, the lone woman, the pastry chef. Her pretty picture appeared regularly in food sections nationwide, the accompanying articles discussing the finer points of piecrust preparation and dishing on the culinary dating scene, her bashful smile not hurting business one bit.

Incognito was a California fusion restaurant, steaks and sweet potatoes cooked with expensive wine and Asian seasonings, so pretty much anything flew for dessert. Upon landing the job, Esmerelda introduced a menu of fried green tea ice cream, eggplant tiramisu, papaya gelatin, Japanese plum cakes, cardamom shrikhand, and, on Sundays, raspberry fortune cookies with home-cooked haikus rolled up inside. Her profiteroles were made of thousands of choux pastry strips woven together, layered squirts of Swiss chocolate cream oozing within; her handmade ice cream was cool on the spoon and warm in the mouth, thick as mashed potatoes; her apple pie cracked with ripe fruit and fresh cinnamon, a dash of saffron spicing the crust.

But the showstoppers were the oatmeal raisin cookies, outrageously lush and creamy, always fresh from the oven and tonguelatheringly soft. Shaped in trapezoids and accompanied by scoops of vanilla ice cream, the cookies were light and rich, complex but simple, sweet yet savory, contradictions that tickled the palate so imaginatively that many diners broke out laughing for sheer joy. The perfume of fresh-baked goods meandered down the alley in which Incognito was housed, the thick, wholesome aroma giving the upscale neighborhood a downright homey feel, grandma’s secret recipe and natural goodness twined up in a perfect, pure dessert.

The French Revolution

The French Revolution